Good morning all!

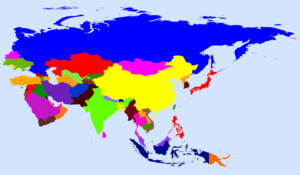

After having presented to you, in turn, the countries that we have chosen for Europe, we pass this week to the second continent that we will visit, Asia. The choice of countries for this huge continent was particularly difficult. At the same time, it had to be in line with our availability (the school calendar has, on the whole, nothing to do with ours and varies enormously from one country to another in connection with religious holidays, the season of rain, suffocating heat periods, etc.), but also with more administrative constraints such as the difficulty or even the impossibility for certain countries to obtain a visa when we have been on the road for several months already and we go to these countries with a journalistic purpose (we had to cross out China from our choices because of these constraints) or the current instability of certain countries and the danger of going there. Eventually, we hope to be able to return to Asia to cover these countries individually, but as part of this first trip we chose to opt for countries where we will be safe and where it will be easier to work. And honestly, out of the number of extremely interesting countries to cover in Asia, it just made our choices a little easier. So over the next few weeks, we will present each of the countries we have chosen (there are 8 of them) and the reasons that led us to select them. But before we get into the specifics of each country, I wanted to give you a global portrait of education in Asia, and especially the challenges that this continent must face. (Please note that the statistics used date from 2015)

An overcrowded and very young continent

Asia is the largest continent in the world, but also the most populous, comprising more than 56% of the world’s population. Of this population of around 4 billion, 1.6 billion are between 0 and 24 years of age a threshold that has never been reached historically for this continent which has never before experienced such a heavy burden of young people of to be educated. In fact, in just one generation, from 1970 to 2010, the Asian population doubled and in the only age group of 5 to 14 years, which represents basic education for several Asian countries, there has a minimum of 647 million young people to attend school. It should be noted that these figures are large approximations since for several countries, the data are extremely difficult to obtain and those which exist are not necessarily reliable. Especially in countries where the education of young girls is still a struggle. They are therefore not always part of the figures given.

To add to the difficulties, Asia is far from being a unified continent. Indeed, the Asian continent is made up of large regional subsystems (South Asia, Southeast Asia, etc.) and brings together both countries which are part of the list of the richest and most advanced countries. the world like Japan and Singapore, and some of the most volatile and least developed countries on the planet, including women’s rights, such as Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Asia remains a continent largely marked by mass poverty and inequalities of considerable magnitude. For example, in Bangladesh, 77% of the population still lives on less than $ 2 a day. This percentage increases to 68% in India, 44% in Vietnam and 28% in China. Needless to say, in the least developed countries, the attendance rate in the classroom and the chances that a child will graduate, or even reach a functional level in reading and writing, are very low. Illiteracy rates are staggering. Some countries, such as Afghanistan, even reach a rate of more than 50% illiterate among young people aged 15 to 24 (again, young girls who have difficult access to education are the most affected.) In all, more than 64 million young people aged 15 to 24 are considered illiterate on this continent.

Another important challenge facing Asia is that of training and recruiting teachers, a job, which depends on the country, is often low paid and little valued. While in 2011 the continent had 15 million primary teachers, it is now estimated that at least 1 million additional jobs will have to be created by 2030 to meet basic needs. Even more if education became accessible to all.

The international impact of these challenges

In 2020, less than a year from now, the developed countries grouped under the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) will represent only 16.5% of the world labor force against 15% for India only and 22.5% for China. In this context, Asia, but also the international community is faced with a real problem. The Asian continent currently represents THE pool of potential workers, but given its choices and its level of development, they must face a very large imbalance in terms of supply and demand. The workers are there, but they have little or no skills. The lack of education partly explains the exploitation often suffered by Asian workers and the very large number of underemployment and hidden unemployment that exist in these countries. But some countries also face the opposite problem. The very low rate of education of the inhabitants makes it extremely difficult to recruit qualified personnel and thus delays the economic development of the country and the vicious circle continues.

And the solutions?

The solutions are all as plural as the realities of the different countries in Asia. But one of them remains universal: investment in education. Indeed, some countries have chosen to prioritize education in their budget and real improvements are being made, some Asian countries have even taken the lead in the ranking since 2012. But the most positive effect of these injections of money is improving the quality of life for residents. For example, 5 countries invest between 21 and 31% of the country’s gross national product (GNP) in education, namely Malaysia, Vietnam, Nepal, South Korea and Thailand, and the impact on economic development is measurable and real. Singapore and Indonesia are also getting closer and closer to this leading group.

In comparison, countries where education is not at the top of the priority list and where spending in this area remains very low (around 9%) stagnate in terms of economic development, but also of rights. This is the case, among others, of Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Burma.

There is also an intermediate tranche to these investments. Several countries invest 10 to 15% of their GNP in education. Their positions remain fragile, but some positive effects are starting to appear. This is the case of India, Laos, Cambodia and the Philippines.

Faced with these unequal public sector investments in education, the relay is often taken by private education, which is experiencing a spectacular boom in certain regions. For example, in Bangladesh, 42% of children attend private school and between 17% and 22% in India, Indonesia and Hong Kong. And if we talk about university studies, it is more than 80% of students from Japan and South Korea who will have to turn to private institutions to continue their education. Although these situations are far from ideal since these schools are not accessible to all, the sums necessary to join these institutions being often very high, they allow an increase in the level of education in the affected countries (pupils whose parents who have to pay for education are often much more diligent in class and go further) and in the long term, according to the researchers, will allow the emergence of an elite who will most likely put education first.

In conclusion

Education in Asia is experiencing great tensions in order to respond to the challenges of a development that we hope is fairer, more united, more balanced and more sustainable. And although these challenges seem considerable, I guarantee you that marvelous projects, bringing hope, are underway in several countries and that we will make you discover some with the greatest pleasure in the coming months.

See you next week,

Genevieve