Apprendre autrement series: travel portion!

One of the things that fascinates me when traveling is all these learnings that have done, and which often come to overturn preconceived ideas or which force us to ask ourselves questions that had never occurred to us before, anyway, the answer seemed obvious to us right? Today, I want to share with you a story that is very far from what I assumed to be the right one: the story of the potato! Given its great importance in the cuisine of northern Europe and the potato crises that created terrible famines and pushed millions of Irish, English and Scots to leave their countries to feed their family, it seemed obvious to me that this food had always been part of their history and came from here, right? What if I told you that, in addition, it was at the origin of the virtual disappearance of the Irish language, also called Irish Gaelic, and of the long fight to preserve it? This is the story I want to share with you today!

The little story of the potato!

The famous tuber that is the basis of Irish, English and Scottish stews and the famous Belgian fries symbol of these countries comes … from South America! More particularly of the western coastal zone where Peru is today. Its history begins a little over 10,000 years ago with that of the Amerindians, hunter-gatherers of the Neolithic era, who lived in this place and who, despite the toxic properties of the potato, succeeded very slowly, to domesticate it, as their lifestyle went from nomad to sedentary. The first known plantations will appear around 8000 years ago in the region of Lake Titicaca.

Whether you classify it in the vegetable or starchy category, you will understand that since it is indigenous to South America, the reign of the ” potato ” cannot go back very far in Europe. And for good reason! It was not until the 16th century that the Spanish Conquistadors returned to port with barrels of corn and potatoes from these distant lands! And even then, they will not be added to the menu of Europeans since they will first be an object of curiosity for botanists and kings and will serve, for clergymen as … medicine! It was not until the beginning of the 17th century that Europeans began to take an interest in it as food and that its culture, although sporadic. It is then the consecration! Not only does this food adapt extremely well to cultivation on European soil, but it can be kept for a very long time, is easy to prepare and is filling. Pushed into the countryside by famines and wars, the culture of the potato will then spread at a crazy speed, winning almost all the countries of Europe as well as Russia since it allows the poorest to eat much more. properly. It will then be considered a miracle food since it will signal the end of famines in Europe. It is even partly attributed to the success of the colonial empires in the 19th century because it enabled the population to acquire food strength and stability, and therefore the army to be more powerful. It will also represent the main support for the industrial revolution because it will allow workers massing in cities to have access to economical and easily accessible food. In a very short time, the potato will have completely transformed the European food landscape and will have become the main food for the majority of the population, mainly in the north of the continent.

The potato crisis

This dependence on a single food will be the cause of one of the worst crises that Ireland has gone through. Indeed, when, in 1845, a parasitic fungus, the ” mildew ” attacks the tubers and destroys, from the first year, more than 40% of the harvest, the whole country is plunged into a famine which will last until ‘in 1852. There is no official count of the number of deaths linked to this crisis, but experts estimate that around 1 million people would have died during this period and 2 million Irish would have left the country for the States United States, Great Britain, Canada and Australia. In just 10 years, the population of Ireland increased from 8 to 6 million inhabitants and the end of the crisis did not stop the disaster, since a large number of Irish continued to flee the country until 1911 The population was then only 4.4 million.

Above, the replica of one of the boats that served to transport thousands of Irish people to North America. It can be visited in Dublin

On the other hand, this crisis, although exceptionally intense, was not the first that Ireland had experienced, which had to face an equally great famine in 1780 without the impact on the country being as great. This time, it was the mismanagement of the crisis that created the scale of what would follow the appearance of this fungus. Because although the potato was indeed the staple food for the vast majority of Irish people, even with 40% loss, there would have been enough food for everyone. But, since 1780, things had changed. Ireland had become a major importer of potatoes, and while, during the first crisis, the ports had been closed, this time, pressure from Protestant traders meant that the Irish ports remained open, and therefore the country continued to export the precious tuber. And while whole families died on the island, convoys of food escorted by the army left for England. Some owners went so far as to expel peasants who, due to the lack of crops, could no longer pay their rent. The crisis was really launched, and since the destruction of the crops continued for the next 3-4 years, even the relief agencies could no longer help.

At the time, the two Ireland were united and were part of the United Kingdom (since 1921, only Northern Ireland is still attached to it and this potato crisis is one of the major reasons that led to the revolt in Republic of Ireland). So we would have expected Queen Victoria, then sovereign of the United Kingdom, to help the people of the island, wouldn’t we? Well, that is not quite what happened. While in 1845 the crisis facing Ireland attracted the attention of the world population and the pope organized a fundraiser for the island, the Ottoman sultan Abdulmecit I declared his intention to send 10,000 euros (a real fortune for the time), for Irish peasants, which the queen refused, demanding that he send only 1000 euros since she herself had given 2000 euros. He therefore complied with his request on the monetary level, but sent this sum accompanied by 3 boats filled with food which ended up arriving in Ireland, but not without having had to face the British soldiers who tried to block them. But why do you do it? Probably to weaken the population which always spoke a language different from English and finally to assert its power in Ireland.

The potato crisis and the decline of Irish Gaelic

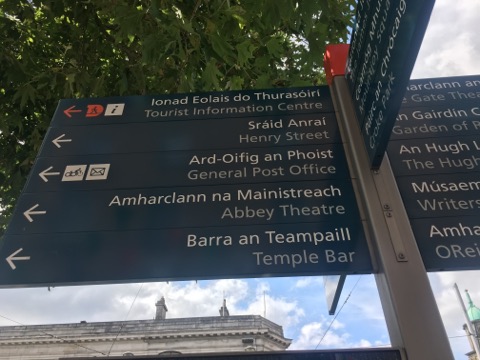

This famine had a catastrophic effect on Irish culture, mainly on its official language, Irish Gaelic commonly known as Irish. Before 1845, 90% of the population spoke this language and considered it their first language. After 1860, they were less than 20%. But what explains this major change in such a short time? You should know that the British Empire had been trying for a long time to make Ireland, English-speaking, which the Irish resisted. But the numerous deaths that resulted from this famine left a very large number of orphans in the country who were placed in English-speaking orphanages where the use of Irish Gaelic was not allowed. Added to this is the fact that a very large number of adults left the country to emigrate to countries where the situation was less difficult, and that those who remained had no choice but to learn to communicate. with the British to get out of the crisis. Irish Gaelic, although still regarded as the first official language in the Republic of Ireland and as a regional language in Northern Ireland, almost disappeared at that time. In fact, it is still in danger since only 2% of the population actually uses it as a first language in everyday life. But many efforts, particularly in the Republic of Ireland, are made to preserve it. At the political level, almost all the ministers of the Irish Parliament, as well as the President, the Prime Minister and the Deputy Prime Minister speak it fluently and give talks in Irish Gaelic. To become a lawyer, you must pass an oral exam in this language and until 2005, it was essential for the police to have a good level of knowledge of the official language. Until 1973, it was compulsory to teach Gaelic in secondary school, but this law fell since the population considered that it was preferable for young people to learn another of the languages of the European Union such as French or German to give them more job opportunities. On the other hand, all pupils who attend state-funded schools must study it, unless they have learning difficulties or have spent many years abroad. Posting in the Republic of Ireland is compulsory in English and Irish Gaelic, and more and more schools where the first language of instruction is Irish Gaelic are emerging in the country. They are called ” Gaelscoileanna ” and they praise their merits by promising that the children who frequent them will be perfectly trilingual (Irish Gaelic, English and French) at the end of their schooling. Today, more than 75,000 children are enrolled and this number is increasing every year. On the other hand, the responsibility to save the language rests entirely on the shoulders of those who are convinced. The bet is not won, but the hope is there.

We hope to have the chance, by the end of the trip, to return to the Republic of Ireland to cover Gaelic schools. But until then, I hope you find this information interesting! Do not hesitate to leave me a comment!

See you soon,

Genevieve